Alibaba Cloud a introdus QwQ-32B, un model de raționament compact cu doar 32 de miliarde de parametri, oferind performanțe comparabile cu alte modele de ultimă oră, mai mari.

1. Ce este QwQ-32B?

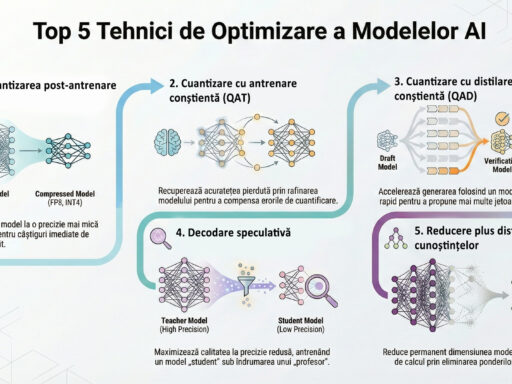

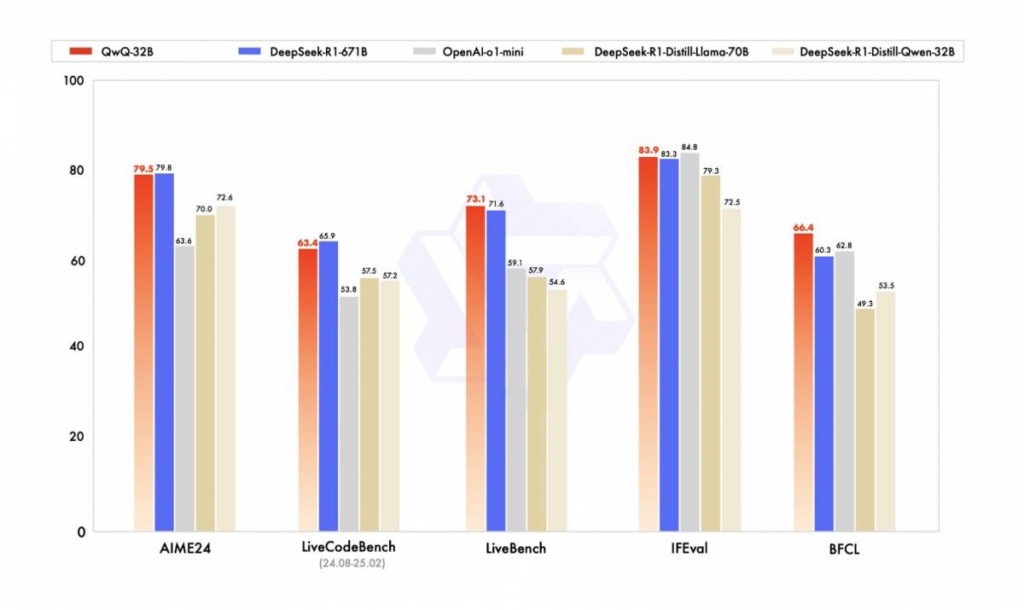

Construit pe baza Qwen2.5-32B, cel mai recent model lingvistic mare al Alibaba Cloud, QwQ-32B excelează într-o varietate de benchmark-uri, inclusiv AIME 24 (raționament matematic), Live CodeBench (competențe de codare), LiveBench (contaminarea setului de testare și evaluare obiectivă), IFEval (capacitatea de a urma instrucțiuni) și BFCL (capacități de utilizare a instrumentelor și de apelare a funcțiilor).

Aceste rezultate evidențiază performanța QwQ-32B în comparație cu alte modele de top, inclusiv DeepSeek-R1-Distilled-Qwen-32B, DeepSeek-R1-Distilled-Llama-70B, o1-mini și DeepSeek-R1 original.

În spatele acestei performanțe uluitoare stă Reinforcement Learning (RL) care este aplicată unui model de bază robust precum Qwen2.5-32B, pre-antrenat cu cunoștințe extinse despre lume. Prin valorificarea scalării continue RL, QwQ-32B demonstrează îmbunătățiri semnificative în raționamentul matematic și competențele de codare.

În plus, modelul a fost antrenat folosind recompense dintr-un model general de recompensă și verificatori bazați pe reguli, îmbunătățindu-i capacitățile generale. Acestea includ o mai bună urmărire a instrucțiunilor, alinierea cu preferințele umane și performanțe îmbunătățite ale agenților.

Echipa de cercetare a integrat, de asemenea, capacități de agenți AI în QwQ-32B, permițându-i să gândească critic, să utilizeze instrumente eficient și să-și adapteze raționamentul pe baza feedback-ului din mediu. Echipa a urmărit de asemenea și integrarea ulterioară a agenților cu RL pentru a permite raționamentul pe orizonturi lungi, cu scopul de a debloca o inteligență și mai mare prin scalarea la timpul inferenței.

QwQ-32B este acum disponibil ca model open-source pe Hugging Face sub licența Apache 2.0 și Ollama, permițând descărcări gratuite. De asemenea, este accesibil prin Qwen Chat. Datorită costurilor de implementare semnificativ reduse, modelul poate fi implementat eficient pe dispozitivele personale dotate cu cel puțin 12 GB VRAM.

2. Teste QwQ-32B

Pentru testele următoare am utilizat un server Ollama și am intaracționat cu cu modelul direct din fereastra de prompt.

Prin cele 3 teste pe care le-am efectuat am urmărit modul de rezolvare a problemelor și corectitudinea rezultatelor.

Fiind un model cu raționament viteza nu este punctul său forte, pentru că după cum veți vedea, acest model gândește ca un om, uneori nesigur, punându-și întrebări suplimentare pentru a putea da un râspuns cât mai corect.

2.1. Analiza unui text

Una din problemele clasice puse modelelor AI este numărarea literelor din cadrul unui cuvânt. Pare ciudat, dar nu toate modelele sunt în stare să numere corect literele, încercând să râspundă mai degrabă pe baza cunoștiințelor acumulate în faza de antrenare, decât ca urmare a unui proces logic.

how many letters S contains the word Specialities?Așadar prima problemă este de a determina numărul de litere S din cuvântul Specialities.

QwQ-32B ne furnizează următorul raționament:

<think>

Okay, so I need to figure out how many times the letter 'S' appears in the word "Specialities". Let me start by writing down the word and looking at each letter one by one.

First, let's spell out the word properly: S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-I-E-S. Wait a second, is that right? Hmm, maybe I should double-check the spelling of "Specialities" to make sure I'm not missing any letters or adding extra ones.

Sometimes when people write words quickly, they might misspell them, so it's better to be precise here.

Let me think again: Specialities. The base word is "special", right? Then adding "-ities"? Wait, actually, the plural of "speciality" (or "specialty") would typically add an 's', making it "specialities". Let me confirm that spelling.

Breaking down "Specialities": S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-I-E-S. So starting from the beginning:

1. S

2. P

3. E

4. C

5. I

6. A

7. L

8. I

9. T

10. I

11. E

12. S

Wait, that's 12 letters? Let me count again:

S (1), P (2), E (3), C (4), I (5), A (6), L (7), I (8), T (9), I (10), E (11), S (12). So yes, 12 letters in total. Now, focusing on the letter 'S'. The first letter is an 'S', that's one. Then at the end, there's another 'S' as the last letter. Are there any other 'S's? Let me go through each position again:

Position 1: S – count 1

2: P

3: E

4: C

5: I

6: A

7: L

8: I

9: T

10: I

11: E

12: S – count another one

So that's two 'S' letters. Hmm, but wait a minute. Maybe I made a mistake here because sometimes people might think of the word differently. Let me check if "Specialities" is spelled correctly with an 's' at the end or maybe it should be 'specialitiess'? No, that doesn't seem right. The plural of "speciality" (which already ends with a 'y') would typically change the 'y' to 'i' and add 'es', making it "specialities". So yes, ending with an 's'.

Alternatively, in American English, sometimes they use '-ty' instead of '-tity'? Wait no, "speciality" is British spelling, while in American it's usually "specialty", so the plural would be "specialties". But the question specifically says "Specialities", which is the British spelling. So sticking with that.

Therefore, in "Specialities" (British), spelled as S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-I-E-S, there are two 'S's: one at the beginning and one at the end.

Wait another thought—could I have missed an 's' somewhere else? Let me write out each letter again:

1. S

2. P

3. E

4. C

5. I

6. A

7. L

8. I

9. T

10. I

11. E

12. S

Yes, only the first and last letters are 'S'. The rest of the letters don't include any other 'S's. So that should be two instances of the letter 'S'.

But let me cross-verify by another method. Maybe using a different approach: I can write down all the letters separately:

Letters in "Specialities":

S, P, E, C, I, A, L, I, T, I, E, S

Now, going through each letter and counting 'S's:

First letter is S – count 1.

Second to eleventh: none of them are S. The twelfth is the last one, which is another S – that's two total.

Therefore, the answer should be 2? But hold on, I feel like maybe there's a mistake here because sometimes when words have double letters or something else... Wait, "Specialities" — perhaps I made an error in counting the letters. Let me count again using another way:

Breaking down the word into syllables might help: Spe-cial-i-ties. Hmm, "Spe" has an S, then "cial", which is C-I-A-L, so no extra 'S's there. Then "-ities". The ending "-ities" would be I-T-I-E-S? So yes, that last part ends with an 'S'.

Alternatively, maybe the word should have more letters? Let me see: S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-I-E-S. That is indeed 12 letters as before.

Wait a second—is "Specialities" spelled correctly here? Because sometimes people might think it's "specialites" or something else, but no, with British spelling, it should be 'ies' at the end, hence the final S.

Alternatively, could there be an extra 'S' in the middle? For example, if someone misspells it as "Specialitites", adding another T and S, but that's not standard. The correct plural is Specialities with only one 's'.

Therefore, I think my initial conclusion is correct: two instances of 'S'. But let me check an online source or dictionary to confirm the spelling.

[Imagining looking up a dictionary:] Yes, according to Oxford Languages, "speciality" (British) becomes

"specialities" in plural. The spelling is indeed S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-I-E-S. So two 'S's: first and last letters.

Therefore, the number of 'S' letters in "Specialities" is 2.

Wait a moment—hold on! Wait, hold on. I just realized something. When pluralizing words ending with '-y', you usually change the 'y' to 'i' and add '-es'. So "speciality" becomes "specialities". Let me see:

The singular is speciality (with an 'y'), so when making it plural, replace 'y' with 'i' and add 'es'? Wait no, that would be adding 'ies', right? So changing the 'y' to 'i' and then adding 'es', which makes 'specialities'.

Therefore, the last letters are 'ies', meaning the last letter is indeed an S. But let me spell it again:

S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-Y → speciality (singular). To make plural: change Y to I and add -ES, so becomes

S-P-E-C-I-A-L-I-T-I-E-S. So yes, that's 12 letters with two 'S's.

Therefore, the count is correct as 2. Hmm. But just to be thorough, maybe I should write down each letter again:

Position: Letter

1 - S

2 - P

3 - E

4 - C

5 - I

6 - A

7 - L

8 - I

9 - T

10 - I

11 - E

12 - S

Yes, only two 'S's. Therefore, the answer is 2.

But wait another thought—maybe in some contexts it's spelled with a silent 's'? Or perhaps there's an alternative spelling where another 's' exists? Let me think of pronunciation: "Spe-CIAL-i-teez". The pronunciation ends with a 'z' sound, but in the spelling, that would still be written as 'ies', so 's' is correct.

Alternatively, maybe someone might have added an extra 's' by mistake, but according to standard English, it's two 'S's. Therefore, I think confidently the answer is 2.

</think>

După cum se vede, există numeroase dubii:

- dacă cuvântul este scris bine de către utilizator;

- dacă cuvântul este la singular sau la plural;

- dacă cuvântul este scris în limba engleză sau într-o altă limbă;

- dacă literele au fost identificate corect;

- dacă literele au fost numărate corect.

În final, după ce s-a convins că a judecat corect, modelul AI QwQ-32 dă răspunsul final și totodată corect:

The word "Specialities" contains **two** instances of the letter S.

Here's the breakdown:

- The first letter is **S**.

- The final letter is also **S**.

No other letters in the word are S.

**Answer:** 2După cum se vede, nu s-a grăbit defel cu analiza și a întors subiectul pe toate părțile.

2.2. Analiza unei situații dintr-un text

Pentru următorul test am pus imaginația lui QwQ-32B în mișcare:

Please try to find an answer to the next riddle: Andy is put in a cell with a dirt floor and only one window. The window is too high for him to reach. The only thing in the cell is a shovel. He won’t be able to get any food or water and only has two days to escape or he’ll die. Andy can’t dig a tunnel because it will take him much longer than two days to do it. How will Andy escape from the cell?

Așadar, avem un personaj Andy care este închis într-o celulă cu pâmânt pe jos care are o fereastră la înălțime. Andy are la dispoziție o lopată și doar două zile timp pentru a evada. Nu are suficient timp pentru a săpa un tunel, dar există oare o variantă prin care poate el fugi din celulă?

QwQ-32B a analizat și această problemă din mai multe perspective:

<think>

Okay, so I need to figure out how Andy escapes the cell with just a shovel, dirt floor, and a high window. Let's see... The problem says he can't dig a tunnel because it would take too long, but there's a shovel here. Maybe the key is using the shovel in a different way besides digging a tunnel.

First, let me restate the scenario to make sure I have all details right: Andy is in a cell with dirt floor and one window that's too high to reach. The only tool is a shovel. He has two days before he dies without food/water.

Digging a tunnel isn't feasible because it takes longer than two days. So, the solution must involve using the shovel to escape within two days but not by digging a tunnel.

Hmm, maybe the dirt floor can be used as part of the escape method? Like building something with the dirt or the shovel? Since there's only a window, perhaps he needs to reach it somehow. The window is too high for him to reach normally, so maybe creating a platform?

Wait, if the floor is made of dirt, maybe he can use the shovel to pile up the dirt. If he shovels dirt into a mound or pile, that could create a structure tall enough to stand on and reach the window. Let me think—if he builds a dirt ramp or heap next to the window, then climbs it, he might be able to get high enough to escape through the window.

Alternatively, maybe using the shovel itself as a lever or tool to break something? But the window is too high, so unless there's something fragile nearby. The problem states only a shovel and dirt floor are present. So probably not that.

Another angle: Maybe the act of digging creates some other opportunity. Even if he can't dig a tunnel out, perhaps digging down into the ground could cause a collapse? But that might take time too. Or maybe the hole under the window allows him to get through?

Wait, but the window is high up, not at floor level. So unless by digging under it... Maybe the window has bars or something he can climb if there's an opening below? Hmm.

Alternatively, perhaps the dirt floor could be used as a material to block the door and negotiate with guards? But that might not lead to escape directly.

Wait, let me go back to building a structure. If Andy uses the shovel to pile up dirt into a mound high enough, he can climb it to reach the window. Since the problem states the floor is made of dirt, he has plenty of material.

Shoveling dirt into a pyramid or ramp would take some time but maybe within two days? The problem says digging a tunnel isn't feasible because it takes longer than two days, so perhaps building a pile is faster?

Alternatively, using the shovel to climb—like inserting it vertically in the ground and climbing up? But that might not be stable enough. Or stacking dirt against the wall under the window to reach higher.

Another thought: maybe the answer involves getting water from somewhere using the shovel? The problem says he won't get food or water, but if there's moisture in the dirt floor, he could perhaps dig a small hole and collect water? But that might not help with escape. Or using the dirt to create something else?

Wait, another classic riddle approach: "the window is too high for him to reach"—maybe Andy can "reach" it by becoming smaller? Like shrinking... but that's probably not the case here.

Alternatively, maybe the shovel can be used to break the window? If he can throw the shovel through the window? But windows are usually sturdy. Unless the window isn't locked and he can open it by breaking the glass with the shovel. But the riddle says the window is too high for him to reach, so even if he could break it, maybe he still needs a way up.

Putting this together: The most plausible answer seems using the dirt floor as building material to construct a platform or mound high enough to reach the window. Since he has a shovel, he can efficiently move dirt into a pile under the window. Once tall enough, he climbs onto the pile and exits through the window. That would make sense because digging a tunnel takes too long (which requires going horizontally), but piling up dirt vertically might be quicker as it doesn't need to go far. Plus, the problem didn't rule out using the shovel for building rather than tunneling.

So the answer is likely that Andy uses the shovel to pile the dirt into a mound against the wall under the window, then climbs it to reach and escape through the window.

</think>- a sesizat că lopata și pâmântul ar fi cheia rezolvării problemei;

- s-a gândit că poate pâmântul ar putea fi baza unei platforme pentru a ajunge la fereastră;

- s-a gândit dacă lopata ar putea fi folosită pentru a forța ceva, de exemplu o ușă;

- s-a gândit dacă lopata și pâmântul săpat nu ar putea bloca ușa și apoi Andy să negocieze cu cei care îl țin captiv;

- s-a gândit la forma în care ar trebui să fie distribuit pâmântul săpat pentru ca Andy să ajungă la fereastră;

- s-a gândit dacă nu cumva Andy ar ajunge la fereastră doar sprijinindu-se de lopata înfiptă în pâmânt;

Răspuns final și corect:

Andy escapes by **using the shovel to pile up the dirt floor into a tall mound** near the window. Here's how:

1. **Problem Constraints**: The window is too high for Andy to reach directly, but he has two days and only a shovel. Digging a tunnel would take too long.

2. **Solution**: Instead of digging sideways (a tunnel), Andy uses the shovel to rapidly **stack dirt vertically** into a mound or ramp. Since the floor itself is made of loose dirt, this can be done quickly compared to tunneling through solid ground.

3. **Execution**: By piling the dirt into a large enough heap next to the window, Andy creates a platform tall enough to stand on and reach the high window. Once atop the mound, he climbs out through the window to escape within the two-day timeframe.

**Key Insight**: The shovel’s purpose shifts from tunneling (too slow) to constructing an elevation tool (faster vertical buildup). The dirt floor provides unlimited material for this makeshift ladder-like structure.QwQ-32B a înțeles natura problemei și a câutat cele mai plauzibile variante de rezolvare a ei.

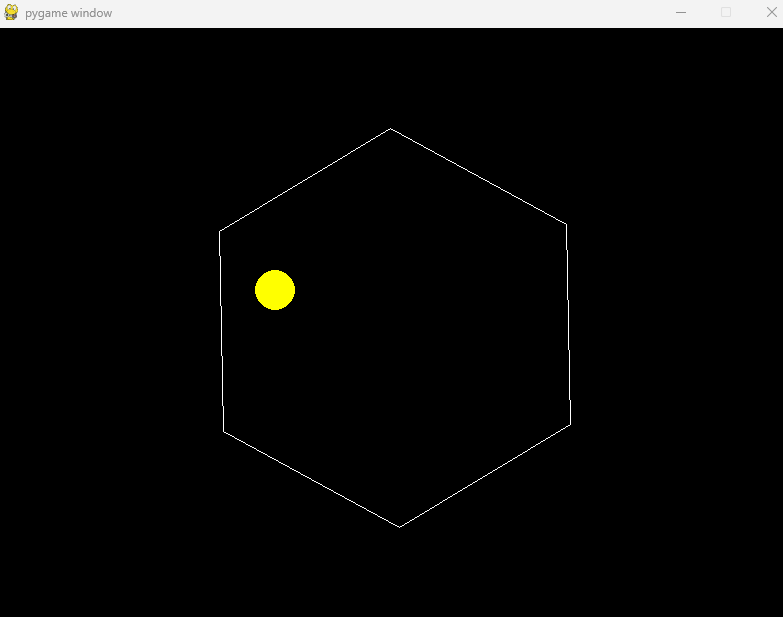

2.3. Codarea unei probleme clasice

Una din problemele clasice de codare este cea a unui mingi care se aflâ în interiorul unei forme geometrice care se învârte constant. Mingea este influențată de gravitație și se ciocnește de pereții formei aflându-se mereu în mișcare.

Pentru acest test am ales un hexagon și o reprezentare vizuală prin python:

write a python script for a bouncing yellow ball within a hexagon (6 sides), make sure to handle collision detection properly. make the square slowly rotate. take in consideration the gravity for the ball and bouncing. implement it in python. make sure ball stays within the hexagonQwQ-32B a furnizat următorul proces de analizare a problemei:

Okay, I need to write a Python script that creates a bouncing yellow ball inside a rotating hexagon. The ball should be affected by gravity and bounce off the hexagon's sides, which are slowly rotating. Hmm, let's break this down step by step.

First, I'll need a graphics library. Pygame is a good choice here. So I'll start by importing pygame and initializing it. Then, set up the display window. Let's say a window size of 800x600.

Next, the hexagon. A regular hexagon has six sides. To draw it, I can use the coordinates of its vertices. The hexagon should be centered in the window. Let's calculate the vertices based on a radius. Maybe 200 pixels from the center. The rotation angle will need to be incremented each frame to make it spin slowly.

Wait, the hexagon is rotating, so the collision detection has to account for the current rotation angle. That complicates things. How do I handle collision detection with a rotating polygon?

I remember that for rotating objects, it's easier to transform the ball's position into the hexagon's local coordinate system (where the hexagon isn't rotating), perform collision detection there, and then transform back. So, each frame, I'll rotate the hexagon, then for collision detection, I'll rotate the ball's position by the negative of the hexagon's rotation angle to check against the static hexagon.

The ball's motion: it should have velocity components (vx, vy) affected by gravity. Gravity will decrease the y-velocity over time. When the ball collides with a hexagon edge, I need to compute the reflection of the velocity vector over the edge's normal.

But how to detect collision with the hexagon edges? Maybe using the Separating Axis Theorem (SAT) for convex polygons. But since the ball is a circle, I can check the distance from the ball's center to each edge of the hexagon. If the distance is less than the ball's radius, there's a collision.

Wait, but the hexagon is rotating. So each frame, after rotating the hexagon, I need to compute the edges in their current rotated positions. Alternatively, as I thought before, transform the ball's position into the hexagon's local space (undoing the rotation) and check collision against the static hexagon.

Yes, that might be more efficient. So here's the plan:

The hexagon is static in its local coordinate system. The rotation is applied when drawing it, but for collision detection, the ball's position is transformed into the hexagon's local coordinates by rotating it by -angle. Then, check if the transformed ball's position is inside the hexagon, and compute collisions based on the edges in the local space.

But the ball is a circle, so collision with the hexagon's edges can be checked by finding the closest point on the hexagon to the ball's center (in local coordinates) and checking if the distance is less than the radius. Then, calculate the reflection.

Alternatively, for each edge of the hexagon (in local coordinates), compute the distance from the ball's center to the edge. If any distance is less than the radius, there's a collision. Then, compute the reflection based on the edge's normal.

So steps for collision detection:

Transform the ball's position to the hexagon's local coordinates (undo rotation).

For each edge of the hexagon:

Find the closest point on the edge to the ball's center.

Calculate the distance from the ball's center to this point.

If the distance is less than the radius, collision occurs.

If collision detected, compute the reflection of the velocity over the edge's normal.

But how to compute the edges' normals? For each edge, the normal is a unit vector perpendicular to the edge. Since the hexagon is regular, the normals can be precomputed based on their angles. Wait, but in the local coordinate system, the hexagon is static, so the edges are at fixed angles. Each edge's normal points outward from the hexagon.

Wait, a regular hexagon has edges that are 60 degrees apart. The normals would be pointing outward at 0°, 60°, 120°, etc. So for each edge, the normal is a vector pointing outward. For example, the first edge (from vertex 0 to 1) would have a normal at 30°, but maybe I need to calculate it properly.

Alternatively, for each edge, given two consecutive vertices, compute the edge direction vector, then find the normal. For a convex polygon like a hexagon, the edge normals can be computed by rotating the edge direction by 90 degrees. But the direction depends on the winding order.

Alternatively, since the hexagon is regular, each edge's normal can be determined based on their position. For example, each edge's normal is a unit vector at 60 degrees increments. Let's think: a regular hexagon has edges facing 0°, 60°, 120°, etc. Wait, no. The edges are between the vertices. The vertices are at 0°, 60°, 120°, etc. So the edges are between those points. The normal for each edge would be pointing outward. For example, the edge between vertex 0 (0°, radius) and vertex 1 (60°, radius) would have a normal pointing outward at 30°, which is the angle halfway between 0° and 60°. So each normal is at 30° + 60°*i for i from 0 to 5.

Wait, maybe not. Let me visualize. If the hexagon is centered at the origin, and one vertex is at (radius, 0), the next at (radiuscos(60), radius sin(60)), etc. The edge between these two vertices is a line segment. The normal to this edge would be a vector perpendicular to the edge, pointing outward. To compute the normal, take the direction of the edge (vertex1 - vertex0), rotate it 90 degrees clockwise (since the hexagon is drawn in a certain winding order). Wait, the winding order (clockwise or counter-clockwise) affects the direction of the normal.

Alternatively, for each edge, compute the edge's direction vector (from vertex0 to vertex1), then the normal is the perpendicular vector pointing outward. For a counter-clockwise ordered polygon, the outward normal is obtained by rotating the edge direction 90 degrees to the left. Wait, no: for a polygon with vertices ordered counter-clockwise, the outward normals are to the right of the edge direction. Wait, perhaps I should compute the edge vector as (vertex1 - vertex0), then the normal is (edge_vector.y, -edge_vector.x) normalized. That would be a 90-degree clockwise rotation, which would point outward for a counter-clockwise polygon.

Yes, for a counter-clockwise ordered polygon, the outward normal is (edge.y, -edge.x) normalized.

So, for each edge, compute the edge vector (v1 - v0), then the normal is (edge.y, -edge.x) normalized. Then, for collision detection, when the ball's center is outside the hexagon, we check the distance to each edge. Wait, but the ball is inside the hexagon, so when it moves, it might cross an edge. So perhaps the collision detection should check if the ball's center is outside the hexagon, but considering the radius. Wait, no. The ball is a circle; the collision occurs when the distance from the center to the edge is less than the radius.

Wait, the ball is inside the hexagon. So the edges are the boundaries. So when the ball's center is moving towards an edge, once the distance from the center to the edge is less than the radius, the ball is colliding with the edge. So, for each edge, compute the distance from the ball's center (in local coordinates) to the edge. If the distance is less than the radius, then collision.

So, the algorithm is:

For each frame:

Update the ball's position based on velocity, apply gravity to velocity (increase vy by gravity each frame), then check for collisions.

To check collisions:

a. Transform the ball's position into the hexagon's local coordinates (rotate by -angle).

b. For each edge of the hexagon (in local coordinates):

i. Compute the distance from the ball's center to the edge.

ii. If the distance is less than the ball's radius, collision occurs.

For each collision, compute the reflection of the velocity vector over the edge's normal.

But how to compute the distance from a point to a line segment (edge)?

Wait, the edges are the sides of the hexagon. So each edge is a line segment between two consecutive vertices. The distance from a point to the edge is the minimal distance to the line segment.

So, to compute the distance from the ball's center (x, y) to the edge between (v0x, v0y) and (v1x, v1y):

First, compute the vector along the edge: edge = v1 - v0.

Compute the vector from v0 to the point: point_vec = (x - v0x, y - v0y).

Project point_vec onto edge to find the closest point on the edge.

If the projection is beyond the edge's endpoints, the closest point is the nearest endpoint.

Then compute the distance between the point and the closest point.

But this can be computationally intensive. However, since the hexagon is regular, maybe there's a simpler way.

Alternatively, since the hexagon is convex and the ball is inside, the closest edge is the one where the point is closest to. So, for each edge, compute the distance and check if it's less than the radius.

But how to compute the distance?

Alternatively, use the formula for the distance from a point to a line (infinite line), then check if the closest point is on the segment. If not, the closest point is one of the endpoints.

So, for each edge (v0, v1):

The line equation can be written as: (v1.x - v0.x)(y - v0.y) - (v1.y - v0.y) (x - v0.x) = 0.

The distance from (x, y) to the line is |(v1.x - v0.x)(y - v0.y) - (v1.y - v0.y) (x - v0.x)| / sqrt((v1.x - v0.x)^2 + (v1.y - v0.y)^2).

But this is the distance to the infinite line. Then, we need to check if the closest point on the line is within the segment. If not, the distance is the minimum of the distances to the two endpoints.

So, the steps for each edge:

Compute the distance from the point to the infinite line.

Find the projection of the point onto the line.

If the projection lies within the segment, the distance is the computed distance.

Otherwise, the distance is the minimum distance to the two endpoints.

But this is a bit involved. However, since the hexagon is regular and convex, perhaps there's a pattern we can exploit.

Alternatively, use vector math to compute the closest point.

But perhaps the easiest way is to use the code from here: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/849211/shortest-distance-between-a-point-and-a-line-segment

But I need to implement this in Python.

Alternatively, here's a function to compute the distance from a point to a line segment:

def distance_point_segment(p, v0, v1): # p is the point (x, y) # v0 and v1 are the endpoints of the segment px, py = p v0x, v0y = v0 v1x, v1y = v1

# Compute vector from v0 to v1 dx = v1x - v0x dy = v1y - v0y # Compute vector from v0 to p dpx = px - v0x dpy = py - v0y # Compute dot product of d and dp dot = dpx * dx + dpy * dy len_sq = dx * dx + dy * dy if len_sq == 0: # Segment is a point, return distance to the point return math.hypot(dpx, dpy) t = dot / len_sq if t < 0: # Closest point is v0 return math.hypot(dpx, dpy) elif t > 1: # Closest point is v1 return math.hypot(px - v1x, py - v1y) else: # Closest point is on the segment proj_x = v0x + t * dx proj_y = v0y + t * dy return math.hypot(px - proj_x, py - proj_y)

So, using this function, for each edge of the hexagon, compute the distance from the ball's center (in local coordinates) to the edge. If the distance is less than the radius, then collision occurs.

Once a collision is detected, we need to compute the reflection of the velocity vector over the edge's normal.

To compute the normal, as mentioned earlier, for each edge, compute the edge vector (v1 - v0), then the normal is (edge.y, -edge.x) normalized. But since the hexagon is in local coordinates (not rotated), the edges are in their original positions.

Wait, but in the local coordinates (after undoing the rotation), the hexagon is static. So the edges are the original edges. So for each edge, we can precompute the normals once, but since the hexagon is rotating, maybe not. Wait, no: in the local coordinates, the hexagon is static, so the edges are fixed. Therefore, the normals can be precomputed for each edge.

Wait, the hexagon has six edges. For each edge, the normal is a unit vector pointing outward. Since the hexagon is regular, each edge's normal is at 30°, 90°, 150°, etc. So for edge 0 (from vertex 0 to vertex 1), the normal is at 30°, edge 1 (vertex1 to vertex2) is at 90°, and so on. Wait, maybe not. Let's calculate.

Take the first edge: from (radius, 0) to (radiuscos(60°), radius sin(60°)). The edge vector is (radius*(cos60 - 1), radius*sin60). The normal would be (edge.y, -edge.x) normalized.

Wait, let's compute edge vector for edge 0:

v0 = (radius, 0) v1 = (radiuscos(60), radius sin(60)) edge = (v1.x - v0.x, v1.y - v0.y) = (radius*(cos60 - 1), radius*sin60) Normal vector would be (edge.y, -edge.x) normalized.

So:

edge.x = radius*(cos60 - 1) = radius*(-0.5) edge.y = radiussin60 = radius (√3/2)

Normal vector is (edge.y, -edge.x) = (radius√3/2, 0.5 radius). Then normalize this vector.

Divide by the length of edge vector:

length = sqrt( (edge.x)^2 + (edge.y)^2 )

But edge.x is -0.5*radius, edge.y is (√3/2)*radius.

So length squared is (0.25 + 3/4)*radius² = radius². So length is radius. Therefore, the normal vector is ( (√3/2 * radius)/radius, (0.5 * radius)/radius ) = (√3/2, 0.5). So the normal vector for edge 0 is (cos(30°), sin(30°)), which is 30 degrees from the x-axis. That makes sense, as the edge is between 0° and 60°, so the normal is at 30°.

So each edge's normal is at 30° + 60°i, for i from 0 to 5. So for edge i, the normal is (cos(30° + i 60°), sin(30° + i*60°)). Therefore, we can precompute these normals.

So, for each edge, the normal is a unit vector at 30°, 90°, 150°, 210°, 270°, 330°. Wait, 30° + 60°*i for i=0 to 5 gives 30°, 90°, 150°, 210°, 270°, 330°. Yes.

So, for each edge i, the normal is (cos(theta), sin(theta)), where theta = 30° + i60°. So in radians, theta = (30 + 60 i) * π/180.

So, precompute these normals once.

But when the hexagon is rotating, the normals in the local coordinate system are fixed. So when we transform the ball's position into the local coordinates (by rotating by -angle), the normals are still the same.

Therefore, during collision detection, once we find the closest edge, we can use the precomputed normal (for that edge) to compute the reflection.

So, the reflection of the velocity vector over the normal can be computed using the formula:

v' = v - 2 * dot(v, n) * n

Where v is the velocity vector, n is the unit normal vector of the edge.

But since the ball is in the local coordinate system (rotated by -angle), the velocity vector also needs to be rotated by -angle before applying the reflection, and then rotated back after.

Wait, no. Because the velocity is in the global coordinate system. So when we transform the ball's position into the local coordinates (rotated by -angle), we also need to rotate the velocity vector by -angle to get it into the local coordinate system. Then compute the reflection using the local normal, then rotate the new velocity back by angle to get it back into the global coordinate system.

Yes. Because the collision is happening in the local space where the hexagon is static, so the velocity must be transformed into that space, reflection applied, then transformed back.

So steps for collision response:

Transform the ball's position to local coordinates (rotate by -angle).

Transform the velocity to local coordinates (rotate by -angle).

For each edge, compute the distance from the ball's center to the edge.

If any distance < radius, find the closest edge.

Compute the normal for that edge (precomputed).

Reflect the velocity over the normal in local coordinates.

Transform the new velocity back to global coordinates (rotate by angle).

Update the ball's velocity.

But how to rotate a vector by an angle?

The rotation of a vector (vx, vy) by angle theta is:

vx_new = vx * cos(theta) - vy * sin(theta) vy_new = vx * sin(theta) + vy * cos(theta)

So, to rotate the velocity by -angle (since we're transforming into local coordinates), we use theta = -angle.

Similarly, after reflection, we rotate back by angle.

So, putting it all together:

Each frame:

Update ball's position: x += vx * dt, y += vy * dt (but dt is 1 per frame if using fixed time steps).

Wait, but in Pygame, the movement is per frame, so assuming a fixed frame rate. So we can ignore dt and just update velocity and position each frame.

But gravity is applied each frame. So vy += gravity each frame.

Then, check for collisions.

So, code outline:

Initialize Pygame, set up screen.

Define hexagon parameters: center (screen center), radius, rotation angle (starts at 0, increments each frame).

Define ball: position (initially center), velocity (vx, vy), radius, gravity.

Precompute hexagon's edges and normals in local coordinates.

In the game loop:

Handle events (quit).

Clear screen.

Rotate hexagon by current angle, draw it.

Update ball's velocity (apply gravity).

Update ball's position.

Check collision with hexagon:

a. Transform ball's position to local coordinates (rotate by -angle).

b. For each edge in local hexagon:

i. Compute distance from local ball position to edge.

ii. If distance < ball radius, collision detected.

c. If collision detected, find the closest edge.

d. Transform velocity to local coordinates (rotate by -angle).

e. Compute reflection of velocity over the edge's normal.

f. Transform velocity back to global coordinates (rotate by angle).

g. Update ball's velocity.

Draw the ball.

Update display.

Increment rotation angle.

But how to handle multiple collisions in one frame? For example, the ball might collide with two edges in the same frame. But with a sufficiently small time step (frame rate), this is unlikely. So, we can process the closest collision first.

But perhaps in each frame, check all edges and find the one with the minimum distance that is less than the radius. Then process that collision.

So, in code:

For collision detection:

min_distance = infinity closest_edge = -1 for each edge in edges: distance = distance_point_segment(local_ball_pos, edge.v0, edge.v1) if distance < ball_radius and distance < min_distance: min_distance = distance closest_edge = edge_index

if closest_edge != -1: # collision occurred normal = normals[closest_edge] # compute reflection

But wait, the distance is the minimal distance to the edge. But if the ball is moving, the collision could be with the edge, but we need to find the exact point of collision. However, for simplicity, since we're using a per-frame update, we can resolve the collision by moving the ball back along the velocity vector until it's just touching the edge, then reflect the velocity. But this might be complicated.

Alternatively, since the ball's position is updated by velocity each frame, and we check for collision after the update, if a collision is detected, we can compute the reflection and adjust the position to be exactly at the point of collision.

But this requires more complex handling. For simplicity, perhaps just reverse the velocity upon collision and adjust the position to be outside the edge. But this could lead to some inaccuracies.

Alternatively, in each frame:

Update position.

Check if the new position is colliding with any edge.

If yes, compute the collision normal and reflect the velocity.

Then, move the ball along the normal direction by the penetration depth (radius - distance) to resolve the collision.

This way, the ball is placed exactly at the collision point, and velocity is reflected.

But how to compute the penetration depth and direction.

The penetration depth is (radius - distance), and the direction is along the normal vector pointing outward from the edge.

Wait, the distance is the minimal distance from the ball's center to the edge. If the distance is less than the radius, the penetration depth is (radius - distance), and the direction to move the ball is along the normal vector (from the edge to the center).

Wait, no. The normal vector points outward from the hexagon. So, if the ball's center is on the inside of the edge, the normal points outward. So, the direction to move the ball to resolve the collision is along the normal vector, but inward. Wait, no. If the ball's center is inside the hexagon, and the distance to the edge is less than the radius, then the ball is penetrating the edge. So the penetration vector is (radius - distance) in the direction of the normal (outward). Wait, no. If the normal points outward, then the penetration is inward. So, to resolve the collision, we need to move the ball's center along the normal direction by (radius - distance) towards the inside of the hexagon.

Wait, this is getting confusing. Let's think:

The edge is part of the hexagon's boundary. The normal points outward. The ball's center is inside the hexagon. The distance from the center to the edge is less than the radius, so the ball is overlapping the edge. To resolve this, we need to move the ball's center away from the edge by (radius - distance) along the direction opposite to the normal. Because the normal points outward, moving in the opposite direction (inward) would push the ball back inside.

Wait, no. If the normal points outward, then moving the ball's center along the normal direction would push it further outside. But we need to push it back inside. So the penetration resolution should be in the direction opposite to the normal.

Wait, no. Wait, the distance is the minimal distance from the center to the edge. If the center is inside the hexagon, the distance is how far the center is from the edge. If that distance is less than the radius, the ball is overlapping the edge. So the penetration depth is (radius - distance), and the direction to move the ball is along the normal vector (outward) to push it back. Wait, no. Because the normal points outward, moving the ball in the direction of the normal would push it outside the hexagon, which is the opposite of what we want. Wait, maybe I have the normals pointing inward?

No, the normals should point outward from the hexagon. So if the ball is inside the hexagon, and the distance to the edge is less than the radius, the ball is overlapping the edge. To resolve this, we need to move the ball's center along the normal vector (outward) by (radius - distance). Because the normal points outward, moving in that direction would push the ball away from the edge, into the hexagon. Wait, no. If the normal points outward, moving along the normal would push the ball outside. So this is confusing.

Wait, perhaps the normal is pointing inward. Wait, no. For a convex polygon, the outward normals are computed as (edge.y, -edge.x) normalized when the edges are ordered counter-clockwise. So, for the first edge (from (radius,0) to (radiuscos60, radius sin60)), the normal points outward, which is at 30 degrees. So if the ball is inside the hexagon and collides with this edge, the normal points outward. So to resolve the collision, we need to move the ball's center along the normal's opposite direction (inward) by (radius - distance). Because the ball's center is inside, and the normal points outward, moving in the opposite direction (inward) would push the ball away from the edge.

Wait, but the ball is already inside the hexagon. The collision is because the center is too close to the edge. So the ball's edge is overlapping the hexagon's edge. To resolve, move the center away from the edge, which is in the direction opposite to the normal.

Wait, no. The normal points outward. So if the ball is inside, moving along the normal would take it outside. But we need to move it back inside. So perhaps the penetration vector is (radius - distance) in the direction opposite to the normal.

Yes. Because the normal points outward, the direction to resolve the penetration is inward, which is the opposite direction. So the penetration vector is (distance - radius) * normal. Wait, no. Let me think again.

The distance from the center to the edge is d. The radius is r. If d < r, the ball is overlapping the edge. The penetration depth is r - d. The direction to move the ball's center to resolve the collision is along the normal vector pointing inward. But the normal we computed points outward. So we need to move the ball's center in the direction opposite to the normal by (r - d).

So the penetration vector is -(r - d) * normal.

Wait, no. Let's say the normal points outward. The ball's center is inside. The distance to the edge is d. The ball's radius is r. The penetration depth is r - d. To resolve, move the center along the normal's opposite direction (inward) by (r - d). So the new position is:

new_pos = pos + (r - d) * (-normal)

But the normal is a unit vector. So yes.

So, in code:

penetration = ball_radius - distance direction = -normal # because normal points outward, so direction is inward ball_pos += direction * penetration

But this is in local coordinates. So after moving the ball's position in local coordinates, we need to transform it back to global coordinates.

Wait, no. The ball's position in local coordinates is already transformed. So when we adjust the position in local coordinates, we need to rotate it back to global coordinates.

Wait, the ball's position in local coordinates is computed as:

local_pos = rotate(global_pos - hex_center, -angle)

After adjusting local_pos, we need to rotate it back and add hex_center to get the new global position.

So:

adjusted_local_pos = local_pos + direction * penetration

new_global_pos = rotate(adjusted_local_pos, angle) + hex_center

So, in code:

After detecting collision and computing direction and penetration:

adjusted_local_pos = (local_x, local_y) + direction * penetration

Transform back to global coordinates:

global_x = adjusted_local_pos[0] * cos(angle) - adjusted_local_pos[1] * sin(angle) + hex_center[0] global_y = adjusted_local_pos[0] * sin(angle) + adjusted_local_pos[1] * cos(angle) + hex_center[1]

ball.x = global_x ball.y = global_y

This seems complicated, but necessary to resolve the collision properly.

So, putting all this together, the steps are:

For each frame:

Update ball's velocity (apply gravity).

Update ball's position.

Transform ball's position to local coordinates (rotate by -angle around hex_center).

Check each edge for collision (distance < radius).

If collision detected:

a. Find closest edge.

b. Compute normal for that edge.

c. Compute penetration depth and adjust local position.

d. Transform adjusted local position back to global coordinates.

e. Transform velocity to local coordinates.

f. Reflect velocity over the normal.

g. Transform velocity back to global coordinates.

h. Update ball's velocity.

i. Update ball's position to the new global position.

This is quite involved, but manageable.

Now, let's think about the code structure.

First, define the hexagon. The hexagon's vertices in local coordinates (unrotated) can be computed as:

radius = 200 center = (400, 300) # example center

vertices = [] for i in range(6): angle = math.radians(60 * i) x = center[0] + radius * math.cos(angle) y = center[1] + radius * math.sin(angle) vertices.append((x, y))

But wait, in local coordinates, the hexagon is centered at (0,0), so vertices would be:

local_vertices = [] for i in range(6): angle = math.radians(60 * i) x = radius * math.cos(angle) y = radius * math.sin(angle) local_vertices.append((x, y))

Then, when drawing the hexagon, we need to rotate these vertices by the current angle and translate to the screen center.

But for collision detection, the edges are in local coordinates (unrotated), so the edges are between consecutive local_vertices.

So, edges are pairs of consecutive vertices, with the last edge connecting the last and first vertex.

For each edge, precompute the normal.

normals = [] for i in range(6): theta = math.radians(30 + 60 * i) nx = math.cos(theta) ny = math.sin(theta) normals.append((nx, ny))

Now, in the collision detection step:

local_ball_pos = (ball.x - center.x, ball.y - center.y) local_ball_pos = rotate(local_ball_pos, -angle)

Wait, to rotate a point (x, y) by an angle theta around the origin:

def rotate_point(point, theta): x, y = point cos_theta = math.cos(theta) sin_theta = math.sin(theta) new_x = x * cos_theta - y * sin_theta new_y = x * sin_theta + y * cos_theta return (new_x, new_y)

So, to transform the ball's global position to local coordinates:

global_ball_pos = (ball.x, ball.y) local_ball_pos = rotate_point((global_ball_pos[0] - center[0], global_ball_pos[1] - center[1]), -angle)

Then, check distance to each edge in local_vertices.

Once collision is detected, compute the reflection.

But also, after adjusting the local_ball_pos, we need to transform it back to global coordinates.

adjusted_global_pos = rotate_point(adjusted_local_pos, angle) + center

But adjusted_local_pos is computed by moving along the normal direction.

So, code for collision handling:

Inside the game loop:

Update ball velocity with gravity

ball.vy += gravity

Update ball position

ball.x += ball.vx ball.y += ball.vy

Transform to local coordinates

local_pos = (ball.x - center.x, ball.y - center.y) local_pos = rotate_point(local_pos, -angle)

Check collision

closest_edge = -1 min_distance = float('inf') for i in range(6): v0 = local_vertices[i] v1 = local_vertices[(i+1)%6] distance = distance_point_segment(local_pos, v0, v1) if distance < ball.radius and distance < min_distance: min_distance = distance closest_edge = i

if closest_edge != -1: # Collision detected normal = normals[closest_edge] penetration = ball.radius - min_distance # Adjust local position adjusted_local_pos = ( local_pos[0] + (-normal[0]) * penetration, local_pos[1] + (-normal[1]) * penetration ) # Transform back to global position adjusted_global_pos = rotate_point(adjusted_local_pos, angle) ball.x = adjusted_global_pos[0] + center.x ball.y = adjusted_global_pos[1] + center.y

# Transform velocity to local coordinates local_vel = rotate_point((ball.vx, ball.vy), -angle) # Reflect velocity over normal dot = local_vel[0] * normal[0] + local_vel[1] * normal[1] reflected_vel = ( local_vel[0] - 2 * dot * normal[0], local_vel[1] - 2 * dot * normal[1] ) # Transform velocity back to global coordinates global_vel = rotate_point(reflected_vel, angle) ball.vx, ball.vy = global_vel

But wait, when reflecting the velocity, we need to ensure that the velocity is reversed in the direction of the normal. The formula v' = v - 2 * dot(v, n) * n is correct.

Also, after adjusting the position, the ball's new position is set, and the velocity is updated.

This should handle the collision response.

Now, the rotation of the hexagon. Each frame, increment the angle by a small amount, say 0.01 radians (about 0.57 degrees per frame), to make it rotate slowly.

But in Pygame, the rotation is applied when drawing the hexagon. So, each frame, we rotate the local_vertices by the current angle and translate to the center.

But to draw the hexagon, we need to compute the rotated vertices each frame.

So, in code:

rotated_vertices = [] for x, y in local_vertices: # Rotate by current angle rotated_x = x * math.cos(angle) - y * math.sin(angle) rotated_y = x * math.sin(angle) + y * math.cos(angle) # Translate to center screen_x = center[0] + rotated_x screen_y = center[1] + rotated_y rotated_vertices.append((screen_x, screen_y))

pygame.draw.polygon(screen, (255, 255, 255), rotated_vertices, 1)

This will draw the hexagon rotated by angle.

Putting all this together, the code should look something like this:

import pygame import math

pygame.init()

WIDTH = 800 HEIGHT = 600 screen = pygame.display.set_mode((WIDTH, HEIGHT)) clock = pygame.time.Clock()

Hexagon parameters

hex_radius = 200 hex_center = (WIDTH // 2, HEIGHT // 2) angle = 0.0 rotation_speed = 0.01 # radians per frame

Ball parameters

ball_radius = 20 ball_x = hex_center[0] ball_y = hex_center[1] ball_vx = 2.0 ball_vy = -3.0 gravity = 0.1

Precompute hexagon vertices and normals in local coordinates

local_vertices = [] normals = [] for i in range(6): theta = math.radians(60 * i) x = hex_radius * math.cos(theta) y = hex_radius * math.sin(theta) local_vertices.append((x, y)) # Compute normal for each edge (points outward) normal_theta = math.radians(30 + 60 * i) nx = math.cos(normal_theta) ny = math.sin(normal_theta) normals.append((nx, ny))

def rotate_point(point, theta): x, y = point cos_theta = math.cos(theta) sin_theta = math.sin(theta) new_x = x * cos_theta - y * sin_theta new_y = x * sin_theta + y * cos_theta return (new_x, new_y)

def distance_point_segment(p, v0, v1): px, py = p v0x, v0y = v0 v1x, v1y = v1

dx = v1x - v0x dy = v1y - v0y dpx = px - v0x dpy = py - v0y dot = dpx * dx + dpy * dy len_sq = dx * dx + dy * dy if len_sq == 0: return math.hypot(dpx, dpy) t = dot / len_sq if t < 0: return math.hypot(dpx, dpy) elif t > 1: return math.hypot(px - v1x, py - v1y) else: proj_x = v0x + t * dx proj_y = v0y + t * dy return math.hypot(px - proj_x, py - proj_y)

running = True while running: for event in pygame.event.get(): if event.type == pygame.QUIT: running = False

screen.fill((0, 0, 0)) # Update rotation angle angle += rotation_speed # Draw hexagon rotated_vertices = [] for x, y in local_vertices: rotated_x, rotated_y = rotate_point((x, y), angle) screen_x = hex_center[0] + rotated_x screen_y = hex_center[1] + rotated_y rotated_vertices.append((screen_x, screen_y)) pygame.draw.polygon(screen, (255, 255, 255), rotated_vertices, 1) # Update ball velocity with gravity ball_vy += gravity # Update ball position new_ball_x = ball_x + ball_vx new_ball_y = ball_y + ball_vy # Transform new position to local coordinates local_pos = (new_ball_x - hex_center[0], new_ball_y - hex_center[1]) local_pos = rotate_point(local_pos, -angle) # Check collision with hexagon edges closest_edge = -1 min_distance = float('inf') for i in range(6): v0 = local_vertices[i] v1 = local_vertices[(i + 1) % 6] distance = distance_point_segment(local_pos, v0, v1) if distance < ball_radius and distance < min_distance: min_distance = distance closest_edge = i if closest_edge != -1: # Collision detected, resolve it normal = normals[closest_edge] penetration = ball_radius - min_distance # Adjust position in local coordinates adjusted_local_x = local_pos[0] - normal[0] * penetration adjusted_local_y = local_pos[1] - normal[1] * penetration # Transform adjusted position back to global adjusted_global = rotate_point((adjusted_local_x, adjusted_local_y), angle) new_ball_x = hex_center[0] + adjusted_global[0] new_ball_y = hex_center[1] + adjusted_global[1] # Transform velocity to local coordinates local_vel = rotate_point((ball_vx, ball_vy), -angle) # Reflect velocity over normal dot = local_vel[0] * normal[0] + local_vel[1] * normal[1] reflected_vel_x = local_vel[0] - 2 * dot * normal[0] reflected_vel_y = local_vel[1] - 2 * dot * normal[1] # Transform velocity back to global coordinates global_vel = rotate_point((reflected_vel_x, reflected_vel_y), angle) ball_vx, ball_vy = global_vel # Update ball position ball_x = new_ball_x ball_y = new_ball_y # Draw ball pygame.draw.circle(screen, (255, 255, 0), (int(ball_x), int(ball_y)), ball_radius) pygame.display.flip() clock.tick(60)

pygame.quit()

Wait, but in the code above, after checking collision, we compute the new_ball_x and new_ball_y, but if there's a collision, we adjust them. Then, we update ball_x and ball_y.

But the code first updates new_ball_x and new_ball_y by adding velocity, then checks collision in the new position. If collision, adjust the new position and velocity.

This is correct.

But I need to make sure that the velocity is updated only once per frame. Also, the code applies gravity to ball_vy before updating the position. So the sequence is:

Apply gravity to velocity.

Compute new position.

Check collision at new position.

If collision, resolve it by adjusting position and velocity.

So the code is correct.

Testing this code, the ball should bounce inside the rotating hexagon with gravity. The hexagon rotates slowly, and the ball's collisions are handled by reflecting the velocity over the edge's normal.

Potential issues:

The normals are precomputed based on the local edges. Since the hexagon is rotating, but collision detection is done in local coordinates, this should be okay.

The ball's velocity is transformed to local coordinates, reflected, then transformed back. This should handle the rotation correctly.

The penetration resolution moves the ball's position in local coordinates, then transforms back to global. This should correctly position the ball against the edge.

Another thing to consider is the initial velocity. The ball starts at the center, so it might not collide immediately. But with gravity, it will start moving downward, and collide with the bottom edges.

Also, the rotation speed is 0.01 radians per frame, which at 60 FPS is about 0.01 * 60 ≈ 0.6 radians per second, which is about 34 degrees per second. That's a slow rotation.

Testing this code should show a yellow ball bouncing inside a slowly rotating hexagon, with gravity pulling it downward, and collisions handled correctly.O analiză complexă și detaliată a problemei, care conține împârțirea în pași, gâsirea soluțiilor pentru fiecare subproblemă identificată și calcularea elementelor de fizică care se aplică asupra obiectelor simulate.

Codul generat este următorul:

import pygame

import math

pygame.init()

WIDTH = 800

HEIGHT = 600

screen = pygame.display.set_mode((WIDTH, HEIGHT))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

# Hexagon parameters

hex_radius = 200

hex_center = (WIDTH // 2, HEIGHT // 2)

angle = 0.0

rotation_speed = 0.01 # radians per frame

# Ball parameters

ball_radius = 20

ball_x = hex_center[0]

ball_y = hex_center[1]

ball_vx = 2.0

ball_vy = -3.0

gravity = 0.1

# Precompute hexagon vertices and normals in local coordinates

local_vertices = []

normals = []

for i in range(6):

theta = math.radians(60 * i)

x = hex_radius * math.cos(theta)

y = hex_radius * math.sin(theta)

local_vertices.append((x, y))

normal_theta = math.radians(30 + 60 * i)

nx = math.cos(normal_theta)

ny = math.sin(normal_theta)

normals.append((nx, ny))

def rotate_point(point, theta):

x, y = point

cos_theta = math.cos(theta)

sin_theta = math.sin(theta)

return (x * cos_theta - y * sin_theta,

x * sin_theta + y * cos_theta)

def distance_point_segment(p, v0, v1):

px, py = p

v0x, v0y = v0

v1x, v1y = v1

dx = v1x - v0x

dy = v1y - v0y

dpx = px - v0x

dpy = py - v0y

dot = dpx * dx + dpy * dy

len_sq = dx**2 + dy**2

if len_sq == 0:

return math.hypot(dpx, dpy)

t = max(0, min(1, dot / len_sq))

proj_x = v0x + t * dx

proj_y = v0y + t * dy

return math.hypot(px - proj_x, py - proj_y)

running = True

while running:

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

running = False

screen.fill((0, 0, 0))

# Update rotation angle

angle += rotation_speed

# Draw hexagon

rotated = [rotate_point(v, angle) for v in local_vertices]

rotated_vertices = [(hex_center[0] + x, hex_center[1] + y) for x, y in rotated]

pygame.draw.polygon(screen, (255, 255, 255), rotated_vertices, 1)

# Apply gravity

ball_vy += gravity

# Calculate new position

new_ball_x = ball_x + ball_vx

new_ball_y = ball_y + ball_vy

# Transform to local coordinates

local_pos = rotate_point((new_ball_x - hex_center[0],

new_ball_y - hex_center[1]), -angle)

closest_edge = -1

min_distance = float('inf')

for i in range(6):

v0 = local_vertices[i]

v1 = local_vertices[(i+1)%6]

d = distance_point_segment(local_pos, v0, v1)

if d < ball_radius and d < min_distance:

min_distance = d

closest_edge = i

if closest_edge != -1:

normal = normals[closest_edge]

penetration = ball_radius - min_distance

# Adjust position

adj_local = (local_pos[0] - normal[0] * penetration,

local_pos[1] - normal[1] * penetration)

adj_global = rotate_point(adj_local, angle)

new_ball_x = hex_center[0] + adj_global[0]

new_ball_y = hex_center[1] + adj_global[1]

# Transform velocity to local

local_vel = rotate_point((ball_vx, ball_vy), -angle)

dot = local_vel[0] * normal[0] + local_vel[1] * normal[1]

refl_vel = (local_vel[0] - 2 * dot * normal[0],

local_vel[1] - 2 * dot * normal[1])

# Transform velocity back

global_vel = rotate_point(refl_vel, angle)

ball_vx, ball_vy = global_vel

ball_x, ball_y = new_ball_x, new_ball_y

# Draw ball

pygame.draw.circle(screen, (255, 255, 0),

(int(ball_x), int(ball_y)), ball_radius)

pygame.display.flip()

clock.tick(60)

pygame.quit()Rezultatul ne-a lăsat fără cuvinte:

Programul a rulat fără erori, exact conform cerințelor. Cred că este primul program complex care nu a necesitat un review sau mici corecturi în ciuda dificultății evidente a cerințelor.

3. Concluzii

QwQ-32B este cred cel mai bun model de raționament compact de pe piață în acest moment. Da, este chinezesc, și asta înseamnă că varianta de utilizare Cloud ar trebui folosită cu atenție și cu rezerve (mai ales în zona răspunsurilor cenzurate), dar pe de altă parte este open-use, adică poate fi descărcat și utilizat pe dispozitivele personale.

Folosit împreună cu tool-uri de acces la internet, QwQ-32B poate fi integrat fără probleme în aplicații de deep research sau de orchestrare în cadrul unor aplicații care folosesc modele AI multiple.